“A leader is someone, anyone, who takes responsibility for finding potential in people and processes, and having the courage to develop that potential.” – Brene Brown

The Research and Development People and Culture Strategy published by BEIS back in July gave a clear message that: Leaders at all levels need to have the right skills to support their teams in developing their careers, and to lead them through major transitions and transformations. It goes on to say: “People are often promoted to leadership roles because of their expertise and reputation within their field. Less consideration is given to the skills and behaviours needed for leadership of people and teams.”

Sound familiar?

The Strategy speaks of a commitment to “ensure leadership and management skills are actively developed and supported in talent programmes and in grant holders’ terms”. But navigating the transition between being a technically competent, excellent researcher to becoming an excellent leader of research and researcher can be challenging for any emerging leader. So what distinguishes leadership from being a great manager or very competent at what you are doing?

Leadership involves change, movement and looking forward. It requires strategic thinking, taking people with you and inspiring them to achieve a vision, but there are other factors at play too. Leadership is a habit that develops over time. It is not a skill or theory we learn on a one-day training course which then equips us to lead. We develop habits by, firstly, noticing the need for change, the benefits of changing, and the costs of not changing. Then we practice something new (thoughts, feelings and actions) little and often. We notice a benefit and this motivates us to continue.

Back in one of the very early ‘Bridging’ sessions I facilitated for the Future Leaders Fellows Development Network, we explored formal theoretical models, considered what leadership actually means in a research context and tried to elicit some of the skills, traits and behaviours that make leadership in research effective.

I strongly believe the FLFs and Innovators in our Network already know what good leadership is, because they have all experienced it in some way, however small or fleeting. They know what it is about that leadership that helped them develop their potential. In the session, participants considered someone whose leadership has had a real impact on them: someone who has enabled their success. In groups, they reflected on what made that leader impactful: what they did, how they behaved, what they said? And how that felt?

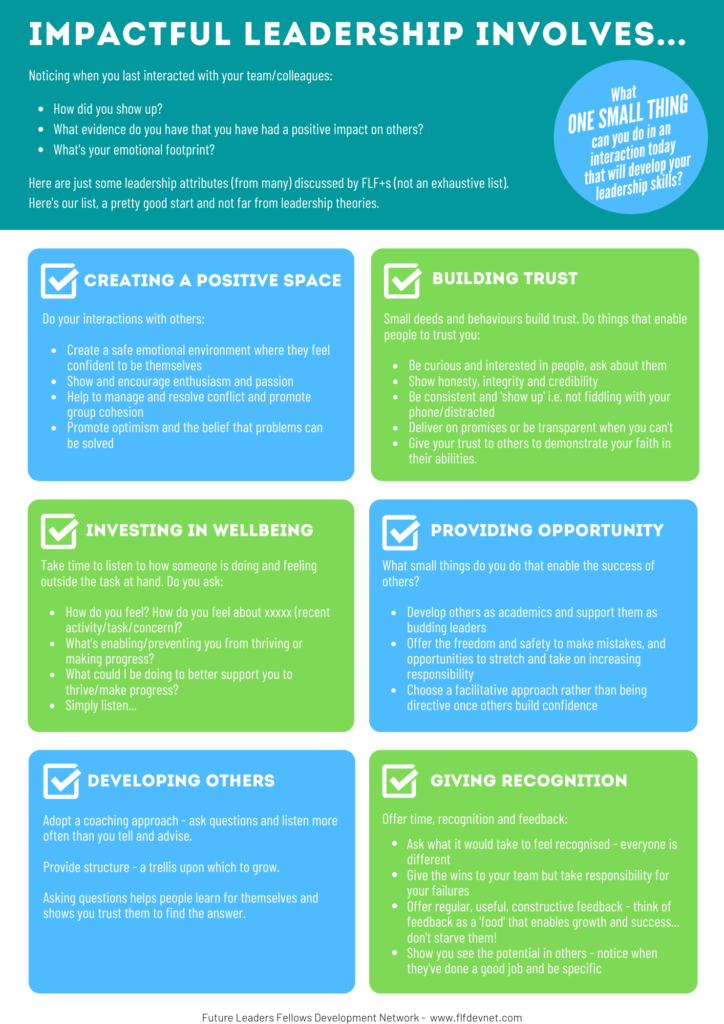

As participants fed back their list of impactful leadership traits to the group, we found they converged around some common themes:

- Creating a positive space

- Building trust

- Investing in wellbeing

- Providing opportunity

- Developing others

- Giving recognition

What strikes me (and repeatedly does so when I facilitate these discussions) is that the list of behaviours, traits and skills identified were predominantly related to emotional intelligence. The impactful leadership the participants described focused on people, rather than on tasks and knowing everything. As an emotional intelligence (EQ) practitioner, I’m naturally rather passionate about emotionally intelligent leadership. The good news is that research shows there is a positive correlation between the measured emotional intelligence of leaders and their performance in a range of success factors.

Would you consider yourself an emotionally intelligent leader? I define EQ as:

- Noticing how you are feeling

- Naming it: What’s going on? Why might you feel like that? What are the impacts on your effectiveness as a leader and researcher?

- Choosing: What is the best way forward? What could be different? What, if anything, needs to change to be more effective?

- Communicating: Letting others know (if appropriate) or communicating and being honest with yourself

The good news is we can develop our EQ. If you want to learn more, we’ll be launching more leadership workshops in 2022 but, in the meantime, here are two books I’d recommend:

- Dare to Lead, by Brene Brown (a very easy read and full of ideas for practices you can try)

- The EQ Edge, Steven Stein & Howard Book (describes elements of EQ and gives practical activities to develop EQ)

“One of the most important applications of EQ is helping leaders foster a workplace climate conducive to high performance. These workplaces yield significantly higher productivity, retention, and profitability, and emotional intelligence appears key to this competitive advantage.” – The Business Case for Emotional Intelligence, Six Seconds

Take a look at our list of impactful leadership skills below, it’s not exhaustive but it’s a great start.

- What would you add to this list?

- Do you see areas of strength or which you need to develop?

- What one small thing could you do in an interaction today that would make your leadership more impactful?

Impactful Leadership download – PDF

Resources

- For members of the FLF Development Network – there is a recording of this workshop ‘Bridging Course #1 – Introduction to Leadership’ on the resources section of the FLFDN website

- Brene Brown’s book ‘Dare to Lead’ is a very engaging read that really brings to life what emotionally intelligent leadership looks like. It’s also grounded in decades of academic research – daretolead.brenebrown.com

- The Trust Equation from Charles Green trustedadvisor.com/why-trust-matters/understanding-trust/understanding-the-trust-equation

- Emotional Intelligence: Six Seconds – a great website full of resources and research: www.6seconds.org

- Emotional intelligence: The EQ Edge – a very accessible book that includes activities to develop EQ: www.pdfdrive.com/the-eq-edge-emotional-intelligence-and-your-success-jb-foreign-imprint-series-canada-e184397151.html

- PDF download of ‘Coaching questions for the GROW model’

- PDF download of ‘Continuum of Leadership’